you likely haven’t heard of some of the best

Whiskey is distilled from a beer (called “wash”) fermented from grain: rye, wheat, corn, barley. This is not the place for a long history of whiskey; instead, a few important topics about what creates quality: fermentation, distillation, flavor, and aging.

Whiskey starts as a beer, made by fermenting various grains: rye, wheat, corn, and barley. You add hot water to the grain(s) and agitate the mixture to convert the starches into sugar (using what’s called a mash tun – see photo); in malt whiskey, the grain (barley) is allowed to sprout, which does the same thing. The quality of the grain is important; so is the “mash bill’, which means what kind and proportion of grain in the mixture: pure rye? Corn and barley? Everyone has their own recipe.

Next, you put the mash into a tank or open vat and introduce yeast, which works to convert the sugars into alcohol. Almost everyone does this quickly (you can heat the mash to speed things up), but actually yeasts prefer to do things slowly, resulting in a more complete and complex fermentation. Different yeasts yield different alcohols, meaning different flavors/aromas in the whiskey. The “drier” (the less residual/ undigested sugar in) the fermentation, the better, but a fully dry fermentation can take a couple of months and hardly anybody wants to wait. This is where practically everyone takes shortcuts. If you use a water-jacketed tank (modern equipment can be better), you can control the speed and completeness of the fermentation.

There are three ways to distill: continuously (and fast), in a column still (also called Coffey after its inventor), which is how a huge percentage of the world’s whiskies are made, including most well-known bourbons, or by single batch in a combination pot and column still such as the German Holstein (a single run, usually some six hours), or in double batch distillation in a variety of pot still designs (four runs, each of 8 to 12 hours). Again, slower is usually better, and double distillation is the best mode for whiskey. The Holstein (photo) is designed for – and best used for – distilling fruit. A lot of craft whiskey distillers use it because it’s cheaper, takes up less space, and is easier and quicker to use than a pot still.

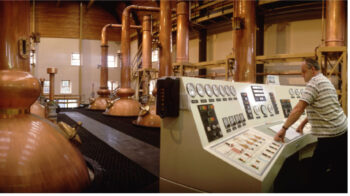

It’s almost impossible to find a photograph of the column stills at any major brand’s whiskey distillery. What you get instead is photos of copper equipment and, mostly, lots of barrels. Here’s what a major rum distillery looks like: the stills are the tall columns with red stripes.. In the mid 1800s, oil refiners learned their trade from alcohol distillers.

This is not about trashing column still production. You can run a column still well and make pretty decent whiskey. Or, like Scotch blended whisky producers, you can blend in malt whiskies distilled on pot stills. But even then, someone making a lot of whiskey can’t pay really close attention.

Here’s a photo inside a famous malt whiskey distillery (500,000 cases/year). Scotch whiskey distillers are not allowed to taste the product while it’s being made.

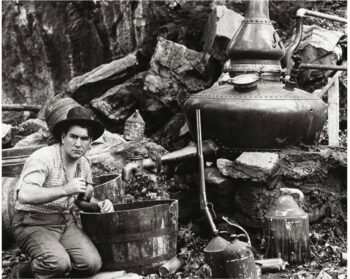

Moonshine, clear whiskey, isn’t aged in barrels. Like most fresh distillates, it’s lighter and often more flowery. It can also be disturbingly crudely alcoholic.

Whiskey is aged in a wide variety of wood barrels, most commonly oak. Aging changes the flavor of whiskey in several ways: by slow oxidation though the medium of the wood staves, by interaction with the wood’s lignins, tannins, and vanillins, by internal chemical changes in the whiskey itself with the passage of time, and — in charred barrels (photo) – by filtration of impurities (most of which shouldn’t be there to start with) by the charcoal layer on the inside of the barrel created by charring.

We encounter very little straight talk about aging. Really good whiskey doesn’t need, or even necessarily improve with, extended aging, and darkness is no indicator of quality. This is also true of cognac/brandy. The photo is our idea how a good whiskey should look: well-distilled flavorful ingredients against a backdrop of oak.

Aging has been hyped to death: telling you that the longer the better (and more expensive), which means that you are often paying for indifferent whiskey that has spent a lot of time picking up oak flavor, to our minds usually too much: you taste oak and alcohol. This is especially true of bourbon, which by regulation has to go into new charred barrels. Most bourbons are over-oaked; that’s about all you taste. Many malt whiskies have caramel added to make them look older. The photo shows a glass of excellent malt whiskey after ten years in a not-new barrel.

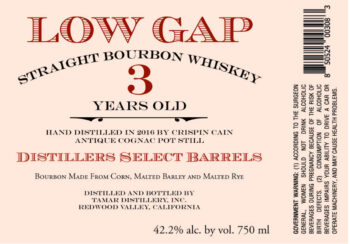

There are further issues, like how and when the whiskey is diluted with water to drinking strength (best practice is to do this slowly over time, but that is rare), but enough for now. The upshot: genuinely good whiskey (let’s say, for starts, one that doesn’t burn when you swallow it), and its ingredients, are treated with expert care at every stage – which is why small-production whiskies can be very good indeed. Some of the best whiskies being made are aged for only 2-4 years: you taste what it was made from instead of a lot of oak. This 3-year-old bourbon wins gold medals in blind tastings against much older whiskies.