PIERRE DE SEGONZAC

Only a few are left, cognac distilleries that for 300 years have distilled wines made from grapes from the distillery’s own vineyard, grapes that they themselves have grown, harvested, and crushed, that they themselves have fermented, year after year. Such distillers know their wines very well, can perfectly adapt their methods to bring out the best in each year’s vintage. We are fortunate to be able to represent this historic spirit.

chalked date is 1974

ONE OF THE FEW SURVIVING ESTATE COGNACS

In the same family since 1702. These cognacs are hand-distilled from grapes grown in the distillery’s small vineyard near Segonzac, home to some of Cognac’s finest grapes.

“Our cellars are not large, but rich in older cognacs. In them are barrels distilled by my great- grandfather” – pablo ferrand

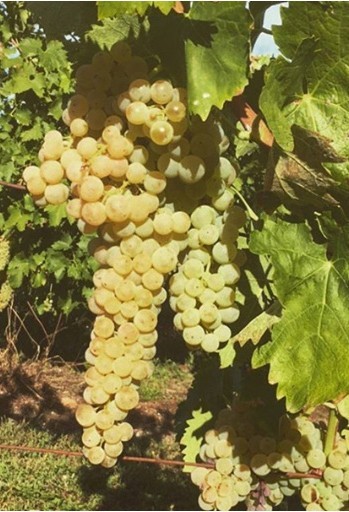

Pierre de Segonzac is an estate cognac. Every grape used for distillation wine comes from the family’s small (19 ½-acre) and carefully tended vineyard next to the distillery (and the house where they live). Grapes grown for distillation into cognac are classified into specific districts according to the quality of their soils. The Grande Champagne district, due to the high content of chalk in the soil, is the highest-rated. Segonzac’s grapes are famous. The circle is the house and distillery; the vineyard is the green patch above and to the left.

Champagne means open countryside: soils so thin that the land is not forested. The famous sparkling wine is called “champagne” for the same reason. These soils are usually mineral (limestone) and produce grapes with high acidity, which distill into cognacs of deep focus that age well. Grapes that struggle to grow have wonderful flavor and complexity.

Harvest is usually late September to mid-October, dates which preserve the high acidity of the estate grapes (100% ugni blanc). The grapes are crushed – gently – in a bladder press, and fermented in two open tanks, each with a different yeast: complexity. The relatively quick fermentation (usually 5-6 days) to absolute dry (zero residual sugar) is important – as is the high acidity – to preserve the quality of the wine. The wine is kept on lees for 3 months as it goes through a natural secondary malolactic fermentation. This old mode – now rare – increases the cognac’s richness and gives it a fuller mouth-feel, especially since the wine is distilled on its lees. Look for this when tasting.

You can FEEL the skill of a master when you visit a great distillery, the atmospheric accumulation over time of constant close attention to every detail.

cognac still at Pierre de Segonzac

The distillery has two copper pot stills: an old 18HL used for the crucial second distillation, and a newer 25HL. This is a large capacity for a distillery of its size: it permits a shorter production time: excellent for maintaining the quality of the wine. Fresher is always better. The stills run 24 hours a day, and it takes less than a month to distill the vineyards’ modest yield. Every cut is by hand and nose.

The low alcohol content of the distilling wine, 9.9-11%, means a concentration factor of seven: seven gallons of wine to make one gallon of cognac fresh from the still. Imagine the richness and complexity of your favorite wine multiplied by seven. It takes six tons of grapes to make a single barrel of cognac.

The shape of the chapiteau, the “hat” on top pf the still, and the graceful curve of the col de cygne, the swan’s neck, influence the amount and quality of rectification, when droplets condense and drop back into the still and thus get further distilled. Cognacs can be subtle or powerful, complex or straightforward, depending on the skill and intent of the man who built the still. The smaller still’s dimpled exterior shows that it was hammered out by hand, likely in the 1930s. It yields cognacs that are precise and subtly complex

Traditional methods mean hands-on work that gives you a deeper understanding of what you’re doing. You develop a non-verbal sense of what’s right or wrong with the process. You tune in. Some modern things are better: propane gives you way more control over your distillation run than a wood fire, but the rush to cut costs and save time has essentially debased most modern commercial spirits production. Taking 10-12 hours per run makes way better distillate than 8-hour cognac-factory shifts. Slowing the still down, making the heads and tails cuts by nose (which takes 20 minutes), allows you to apply hundreds of hours of direct experience, and years of living with the results: get it wrong, and you have diminished an entire barrel of cognac.

Aging is in standard 350-liter cognac barrels; theirs are Limousin oak. Relatively few of the barrels are new: the family believes in cognacs that are lightly oaked: oak as a backdrop to the complex and varied flavors and aromas so beautifully focused and enriched by distillation.

All of this means very little absent the skills, talent, and knowledge of the distiller and cellar-master. The family has been carrying on its traditions since 1702, knowledge and expertise learned from hands-on work at every level handed from father to son to grandson: how best to tend grapes, the precise time to harvest, use of yeasts, modes of distillation, adjusting techniques to suit the wines of the current vintage, secrets of aging and blending specific to cognac from their own grapes: this cannot be duplicated.

It’s how great spirits are made